If we own or manage a building in New York City that’s more than six stories, Local Law 11 isn’t optional, it’s one of the most important safety and compliance rules we live with.

Local Law 11, formally known as the Facade Inspection & Safety Program (FISP), exists because pieces of masonry, terra cotta, or loose railings have fallen in the past and injured people on the street. The law forces us, as owners and managers, to inspect and maintain exterior walls on a predictable cycle instead of waiting for a crisis.

In this guide, we break down in plain language when NYC buildings must inspect the facade, how Local Law 11 works, what happens if we miss deadlines, and how to stay ahead of DOB violations, HPD complaints, and costly long‑term sidewalk sheds.

We’ll focus on practical steps, what we actually have to do, when, and who we need to hire, so Local Law 11 becomes a manageable capital program instead of a constant emergency.

What Is Local Law 11 And Why It Matters For NYC Buildings

Local Law 11 is New York City’s primary facade safety law. It’s part of the NYC Administrative Code (Article 302) and DOB Rule 1 RCNY 103‑04. Collectively, these rules create the Facade Inspection & Safety Program (FISP).

At its core, Local Law 11 does three things:

- Requires regular facade inspections for buildings over six stories.

- Forces owners to fix unsafe conditions before they endanger the public.

- Creates a paper trail with DOB so the City can track compliance and enforce penalties if we fall behind.

The law applies citywide, Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island. If we think of NYC building violations as a risk landscape, Local Law 11 sits at the intersection of safety, liability, and long‑term capital planning.

A few reasons it matters so much:

- Liability exposure – When a chunk of facade falls and injures someone, lawyers ask one question first: Were Local Law 11 inspections current and were recommendations followed?

- Insurance and financing – Lenders, buyers, and insurers increasingly ask for recent FISP reports and open DOB violations before closing a deal or renewing coverage.

- Budget predictability – Facade systems age. If we treat Local Law 11 as a recurring capital project every five years, we’re in control. If we ignore it, we end up with emergency repairs, HPD complaints for related water infiltration, and years‑long sidewalk sheds.

For the legal basics and current rule text, DOB’s facade safety page is the primary reference point: https://www.nyc.gov/site/buildings/safety/facades.page.

Which Buildings Are Covered Under Local Law 11

The threshold is surprisingly simple:

If our building is greater than six stories, Local Law 11 applies.

That includes:

- Rental apartment buildings

- Cooperatives and condominiums

- Office and commercial towers

- Mixed‑use buildings

- Institutional buildings (schools, hospitals, religious buildings) over six stories

A few nuances we see trip people up:

- Stories are counted above the basement. A basement usually counts as a story if more than half its height is above grade: a cellar typically does not. That distinction can push a “six‑story” building into the “greater than six stories” category.

- Penthouse levels and mechanical floors count if they’re above the main roof.

- Landmarked buildings are not exempt. In fact, they typically need even more careful planning because any facade repairs can require Landmarks approval.

If we’re unsure whether our property truly crosses the threshold, most owners check:

- The Certificate of Occupancy

- DOB’s Building Information System or DOB NOW

- Our architect’s interpretation of how floors are counted under the Building Code

From a risk standpoint, it’s safer to assume coverage and confirm with a professional than to operate as if Local Law 11 doesn’t apply and discover it after a DOB inspection or a serious incident.

For quick background on our open DOB violations and related NYC building violations across agencies, tools like ViolationWatch give us a consolidated picture before we jump into facade planning.

Understanding Local Law 11 Inspection Cycles And Deadlines

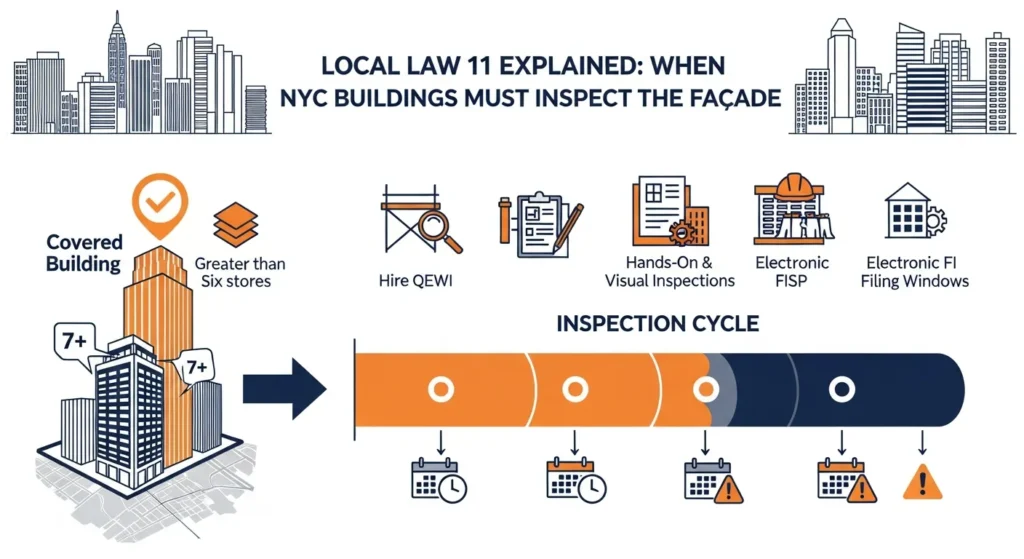

Local Law 11 runs on repeating five‑year cycles. Every cycle is broken into three sub‑cycles, and each building is assigned to one of those windows based on its block and lot number.

How the cycles work

- Cycle: A five‑year period during which all covered buildings must be inspected and filed.

- Sub‑cycle: A specific filing window within that five‑year period. Our deadline depends on the last digit of our block number.

DOB publishes the official schedule for each cycle, including which block numbers file when. That schedule is on the same facade safety page mentioned earlier. Missing our assigned window is what triggers DOB violations and late‑filing penalties.

What has to happen within the cycle

For every cycle, the owner must:

- Hire a Qualified Exterior Wall Inspector (QEWI), a NY‑licensed professional engineer (PE) or registered architect (RA) with at least seven years of relevant facade experience and DOB qualification.

- Complete the inspection following the hands‑on and visual survey rules.

- File the FISP technical report electronically with DOB within the building’s sub‑cycle deadline.

- Address SWARMP or Unsafe conditions on the schedule the QEWI sets and DOB approves.

We can file early in our window. Waiting until the last month is how we end up paying a premium for scaffolding and professional fees, or worse, missing the deadline entirely.

To keep the calendar straight, many owners now pair their internal tracking with external monitoring. For example, we can get building violation alerts when new DOB or HPD issues appear by registering at https://violationwatch.nyc/register/. Staying ahead of NYC building violations gives us more time to sequence facade work intelligently rather than reactively.

Critical Time Triggers: When Your Facade Must Be Inspected

The main trigger is simple: our assigned sub‑cycle window every five years. Within that period, the inspection must be completed and the report filed.

But real life is messier than a clean five‑year rhythm. There are other moments when a facade inspection, or at least a targeted review, becomes urgent.

1. Discovery of new defects

If we notice, or a tenant reports, any of the following, we should call our QEWI or another facade professional immediately:

- Cracks that widen over time

- Spalled brick or concrete (surfaces flaking, popping, or shedding pieces)

- Rust‑stained or deflected lintels

- Loose or shifting stone units

- Water infiltration linked to facade elements

- Wobbly balcony railings or loose metal panels

Under the Local Law 11 framework, conditions that present immediate danger can change a building’s facade status to Unsafe at any time, even in the middle of a cycle, which triggers immediate protection and repair obligations.

2. After severe weather or impact events

Major storms, high‑wind events, or vehicular impacts into building corners or loading docks can destabilize exterior walls. When we see unusual cracking or displacement after a storm, a focused facade check is good risk management, even if the law doesn’t explicitly demand a new full‑building inspection right away.

3. When we undertake major exterior work

Large‑scale work like window replacement, balcony repairs, or roof replacement may:

- Expose hidden facade defects

- Change drainage paths and accelerate deterioration elsewhere

- Require coordination with our QEWI so repairs and Local Law 11 classifications stay consistent

DOB can also tie permit close‑out to addressing open facade violations.

4. DOB inspections and complaints

If DOB responds to a 311 complaint or a field inspector observes loose masonry, the agency can issue:

- Immediate DOB violations

- Orders to install protection such as sidewalk sheds

- Requirements to have a QEWI investigate and report

We see a similar pattern with HPD complaints when water penetration or interior damage traces back to the envelope. The fastest way to know if such issues have already landed on our property is to run a quick search using a NYC violation lookup tool and then plan the necessary follow‑up.

In short, Local Law 11 inspections are cyclical by design, but the facade doesn’t wait for the calendar. Any sign of instability is effectively a trigger to act.

Key Steps In The Local Law 11 Facade Inspection Process

Once we’ve confirmed that Local Law 11 applies and know our sub‑cycle window, the real work starts. A good QEWI will walk us through the process, but it helps to know the typical playbook.

1. Select and retain a QEWI

Our QEWI must be:

- A New York‑licensed professional engineer (PE) or registered architect (RA)

- With at least seven years of relevant facade experience

- Accepted by DOB as a Qualified Exterior Wall Inspector

We’ll dive deeper into selection later, but we should treat this like hiring a lead consultant for a multi‑year capital program, not a one‑off report writer.

2. Pre‑inspection review and access planning

Before anyone goes up on a scaffold, the QEWI usually:

- Reviews prior FISP reports and DOB records

- Checks for open NYC building violations and HPD complaints related to water or structure

- Walks the site at street level to understand access constraints

Then we coordinate access:

- Sidewalk sheds and suspended scaffolds (“drops”)

- Roof rigging points and parapet access

- Interior access to balconies, terraces, and setback roofs

Access is a major cost driver. Planning early lets us combine work, for example, doing masonry repairs and window sealant at the same time.

3. Visual survey of all exterior walls

Local Law 11 requires the QEWI to conduct a visual examination of all exterior walls and appurtenances (balconies, fire escapes, railings, decorative elements, etc.). This includes:

- Street facades

- Side and rear yards

- Courtyards and shafts, where visible

Drones are sometimes used for preliminary assessments but do not replace the required hands‑on examinations.

4. Hands‑on examinations every 60 feet

The law mandates that the QEWI perform hands‑on examinations at intervals not exceeding 60 feet along facades that face a public right‑of‑way, from grade to the top of the building. That typically means:

- Suspended scaffold drops at planned locations

- Close‑up tapping, probing, and visual checks of masonry, stone, terra cotta, and metal

- Checking connections and supports for balconies, railings, and overhangs

Since 2024, the rules specifically require close observation of parapets along public rights‑of‑way, regardless of building height. Even buildings below the six‑story FISP threshold now have a parapet responsibility.

5. Probes and targeted investigations

Where the QEWI suspects hidden defects, for example, corroded shelf angles behind brick, they may direct localized probes. This can mean:

- Removing brick or stone in sample areas

- Inspecting steel and backup walls

- Testing anchors, railings, or facade attachments

Probes add cost but often save money in the long run by preventing sudden failures and unplanned emergency work.

6. Classification and report preparation

After the field work, the QEWI classifies each facade as Safe, SWARMP (Safe With a Repair and Maintenance Program), or Unsafe, and prepares the technical report.

The report includes:

- Building information and height

- Inspection methods and locations of hands‑on examinations

- Photos and descriptions of defects

- The overall status classification

- Required repairs and deadlines, particularly for SWARMP items

This report is filed electronically with DOB and becomes part of the building’s permanent compliance record.

Consequences Of Missing Local Law 11 Inspection Deadlines

Local Law 11 has teeth. When we miss inspection windows or ignore required repairs, DOB can layer on penalties that quickly dwarf the cost of doing the work on time.

DOB violations and civil penalties

Owners can be penalized for:

- Late or missing FISP reports

- Failure to correct Unsafe conditions within the prescribed time frame

- Failure to maintain protections (like sidewalk sheds) that were ordered for public safety

DOB’s rules set out per‑month fines for late filings and ongoing Unsafe conditions. Plus, there are fees tied to how long sidewalk sheds remain in place, especially when they linger with no visible progress.

The longer we delay, the more problems stack up:

- Additional DOB violations on the same condition

- Tougher scrutiny from plan examiners when we file other alteration permits

- Difficulty with refinancing, sale, or insurance renewals

DOB’s enforcement bulletins and penalty schedules are public: the agency routinely publishes updates on enforcement priorities: https://www.nyc.gov/site/buildings/index.page.

Stop Work Orders and emergency actions

For serious hazards, DOB can issue a Stop Work Order on portions of a project or building operations until structural stability and protection are confirmed. In extreme cases, DOB can:

- Order emergency shoring or bracing

- Mandate immediate installation of a sidewalk shed, netting, or fencing

- Pursue additional enforcement through the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings (OATH)

Beyond legal consequences, there’s reputational and operational damage: street‑front retail under dark sidewalk sheds for years, tenants frustrated by noise and dust, and HPD complaints related to leaks and drafts that stem from unresolved facade problems.

To avoid surprises, we can set up building violation alerts so we’re notified as soon as new DOB or HPD issues hit our building’s record. Get instant alerts whenever your building receives a new violation, sign up for real-time monitoring at https://violationwatch.nyc/register/.

Planning Ahead: How Building Owners Can Stay On Schedule

Treating Local Law 11 as a recurring capital plan, not a one‑off emergency, is the single biggest shift that separates proactive owners from those constantly under sheds.

Here’s how we structure that plan.

1. Calendar the cycle now

We start by confirming:

- Our building’s block and lot (BBL)

- Its assigned FISP sub‑cycle filing window

- The last time a report was filed and its status (Safe, SWARMP, or Unsafe)

Then we put calendar reminders 18, 12, and 6 months before our filing deadline. At 18 months, we start talking to QEWIs. At 12 months, we lock in access plans.

2. Run a pre‑cycle condition review

A year or two before the official inspection, we’ll often have a lighter condition review done:

- Limited hands‑on checks at known trouble spots

- Review of tenant complaints (leaks, drafts, cracks)

- Targeted infrared or moisture scanning where appropriate

This early look lets us:

- Bundle work with other exterior projects (roofing, window replacement)

- Decide whether to phase repairs over two fiscal years

- Avoid last‑minute panic when the official deadline hits

3. Budget for access and repairs

In each five‑year cycle, we assume costs for:

- Access: sidewalk sheds, suspended scaffolds, hoists, lifts

- Professional services: QEWI fees, probes, testing, report filings, amendments

- Construction: masonry repointing, lintel replacement, parapet rebuilding, coating/repairs

We’ve found it helpful to treat facade work almost like a reserve study in a condo or co‑op: a predictable recurring obligation tied to the building’s age and cladding type.

4. Integrate with overall NYC property compliance

Facade issues rarely exist in a vacuum. The same leaks that deteriorate brick can trigger:

- HPD complaints from tenants

- Mold and housing maintenance violations

- Energy performance issues when insulation gets saturated

We try to look at Local Law 11 as part of a broader NYC property compliance strategy. A regular scan of our building’s record using a NYC violation lookup tool keeps us from being blindsided by related enforcement.

For free lookups, use our NYC violation lookup tool and then loop in the QEWI or managing agent to plan repairs and filings in a coordinated way.

Working With Qualified Professionals For Local Law 11 Compliance

The quality of our QEWI and project team often determines whether a Local Law 11 cycle is uneventful or miserable.

Why the QEWI matters so much

Unlike many compliance filings, a FISP report is not just a form. The QEWI’s judgment call, Safe, SWARMP, or Unsafe, directly shapes:

- The urgency and scope of repairs

- How much time we have to complete them

- The likelihood of future DOB questions or audits

We want someone who’s conservative enough to protect the public and our liability, but practical enough to phase work intelligently and avoid over‑classification of minor conditions.

Coordinating engineers, contractors, and building staff

A successful Local Law 11 program typically involves:

- QEWI as the lead professional

- Contractor experienced in facade and access work

- Owner’s rep or property manager to coordinate tenants and operations

Our internal team should understand:

- When noisy work will occur

- Which entrances or sidewalks might be narrowed or detoured

- How to handle delivery schedules and trash pickup around sidewalk sheds

On larger properties, we sometimes schedule work facade by facade to minimize disruption to ground‑floor retail, schools, or healthcare tenants.

For owners juggling multiple assets, centralizing tracking through a platform like ViolationWatch can help us monitor DOB violations, HPD complaints, and facade filing statuses across the portfolio in one place.

Conclusion

Local Law 11 isn’t going away. If anything, inspections are getting more detailed as buildings age and the City tightens enforcement. The most resilient owners treat facade work as a normal part of operating in New York, not as an occasional crisis.

Below, we pull together the core pieces we need to manage, from how QEWIs classify our building to what happens after the report is filed.

The Three Facade Status Categories: Safe, SWARMP, And Unsafe

Every FISP report assigns one of three statuses to each exterior wall system:

- Safe – No hazardous conditions and no foreseeable issues that could become unsafe before the next cycle if normal maintenance is performed.

- SWARMP (Safe With a Repair and Maintenance Program) – The facade isn’t currently dangerous, but there are defects that will need to be repaired before the next cycle according to a schedule set by the QEWI.

- Unsafe – One or more conditions present an immediate danger to people or property (for example, loose masonry, failed terra cotta units, unstable parapets, or compromised balcony railings).

From a planning perspective:

- A Safe rating doesn’t mean we can ignore the envelope for five years. Routine maintenance still matters.

- SWARMP is where we have the most control. If we use the entire cycle wisely, we can schedule repairs, rebid work, and avoid emergency pricing.

- Unsafe is the red zone: it triggers protections and hard deadlines.

We should always know our current classification and what deadlines are attached to past SWARMP items.

Required Inspection Methods And Typical Scope Of Work

Local Law 11 is very specific about how inspections are done:

- Visual examination of all exterior walls and appurtenances.

- Hands‑on examinations at least every 60 feet along public‑facing facades, from grade to roof.

- Close‑up review of parapets along public rights‑of‑way, regardless of building height.

Typical scope on a mid‑ or high‑rise building includes:

- Multiple scaffold drops per facade

- Close inspection of:

- Brick, stone, and terra cotta units

- Shelf angles, lintels, and exposed steel

- Balconies, railings, and canopies

- Fire escapes and their connections

- Probes where underlying steel or anchors are suspect

On the repair side, we often see:

- Repointing mortar joints

- Replacing cracked or displaced masonry units

- Installing new lintels or shelf angles

- Rebuilding parapets and coping stones

- Repairing coated systems or curtain walls

The inspection is meant to uncover these needs early enough that we can phase and fund them instead of waiting for emergency failures.

Required Submissions To DOB After The Inspection

Once the QEWI completes the inspection, they must electronically file a FISP technical report with DOB. That report includes:

- Building identification (address, block and lot, building height, occupancy)

- Description of inspection methods, drops, probes, and parapet reviews

- Photo documentation of representative conditions

- A detailed defect log and mapping of locations

- The final classification: Safe, SWARMP, or Unsafe

- A timeline for addressing each SWARMP item

Plus, DOB expects follow‑up filings when conditions change:

- Amended reports – If new information emerges or the scope of repairs changes.

- Cured reports – After Unsafe conditions have been fully repaired and verified.

All of this becomes part of our building’s permanent NYC property compliance history. Prospective buyers, lenders, and even journalists can (and do) pull this information.

Violations, Fines, And Stop Work Orders

When we miss a filing or fail to address an Unsafe condition, DOB can issue:

- Class 1 or Class 2 DOB violations related to facade safety

- Civil penalties for late reports and prolonged Unsafe conditions

- Additional fines tied to extended sidewalk shed durations

If inspectors believe the public is at risk, they can impose a Stop Work Order on part of our project or the building until hazards are mitigated.

Remember that DOB violations rarely exist in isolation. A visible, deteriorated facade often correlates with HPD complaints for leaks, drafts, and mold, especially in residential buildings. HPD’s complaint portal, https://www.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/complaints.page, gives a useful snapshot of tenant‑reported conditions that may point back to facade issues.

From a control standpoint, we want to know about problems the moment they’re issued. Setting up building violation alerts through a monitoring service helps us respond before penalties escalate or headline‑making enforcement actions occur.

Emergency Protections And Sidewalk Sheds

For Unsafe classifications, DOB expects immediate action to protect the public. That usually means:

- Installing a sidewalk shed along affected elevations

- Adding fencing, netting, or other barricades as appropriate

- Restricting access beneath dangerous sections (setback roofs, courtyards, balconies)

These protections must go up quickly, often within days, and stay in place until repairs are completed and the QEWI submits a Cured report.

The irony is that sidewalk sheds themselves attract scrutiny. The longer they stay, the more questions DOB asks about progress. Extended sheds can trigger extra fees and community frustration.

The most effective strategy we’ve seen is simple: if a shed goes up, we move repairs to the top of the priority list and keep clear documentation of progress so DOB inspectors see forward motion, not stagnation.

Budgeting For Recurring Inspection Cycles

Facade work is expensive, but it’s far cheaper as a planned program than as a string of emergencies. When we budget, we break it into three buckets each cycle:

- Professional and compliance costs

- QEWI retainer

- Probes, testing, and report preparation

- DOB filing fees and potential amendments

- Access and safety costs

- Sidewalk sheds

- Suspended scaffolds, hoists, and rigging

- Flaggers and temporary street occupancy permits

- Repair and construction costs

- Masonry repair and replacement

- Steel repairs (lintels, shelf angles)

- Parapet, balcony, and railing work

On older masonry buildings, it’s realistic to expect substantial facade work at least every other cycle. We plan reserves and long‑term capital schedules accordingly, particularly in co‑ops and condos where assessments can be sensitive.

Coordinating With Tenants And Operations

Even the best technical plan fails if we ignore day‑to‑day building life.

Our operational checklist typically includes:

- Advance notices to residents and commercial tenants about:

- Scaffold installation dates

- Anticipated noise and hours of work

- Window covering or access requirements

- Coordination with retail to protect storefronts, signage, and curbside deliveries

- Security checks when new scaffold access appears near windows or roofs

We’ve seen projects go much smoother when managers hold a brief Q&A session or send a clear, jargon‑free memo explaining why Local Law 11 work is happening and how long it should last.

Transparent communication reduces complaints to 311 and HPD, which in turn lowers the odds of overlapping inspections and additional NYC building violations.

Choosing A Qualified Exterior Wall Inspector (QEWI)

Selecting the right QEWI is part technical decision, part trust decision.

We look for:

- Current DOB qualification as a QEWI with an active license in New York

- A strong track record of FISP report filings, including buildings like ours in size, age, and construction type

- Clear, written inspection methodology (number of drops, probe strategy, parapet access)

- Comfort dealing with Landmarks Preservation Commission, if the building is designated

- A communication style that our board, owners, or asset managers understand

We also confirm that the QEWI’s proposed scope includes not just the report, but reasonable support during bidding and construction so field conditions and paperwork stay aligned.

What To Ask Your Engineer Or Architect Before Hiring

Before we sign, we make sure to ask a few specific questions:

- Are you currently DOB‑qualified as a QEWI, and how many FISP reports have you filed in the last cycle?

- Have you worked on buildings similar to ours? (e.g., brick high‑rise with balconies, terra cotta landmark, curtain wall tower.)

- What is your proposed inspection plan?

- How many scaffold drops do you anticipate?

- How will you access parapets and difficult rear yards?

- Do you foresee the need for probes, and where?

- How do you distinguish between SWARMP and Unsafe? We want them to explain their philosophy on risk and phasing.

- What’s included in your fee?

- Initial inspection and base report

- Amended and Cured reports

- Construction administration (site visits, RFIs, change orders)

- DOB interactions and responses to questions

- How will you help us control long‑term costs?

- Bundling work across cycles

- Coordinating with other capital projects

- Reducing shed duration

A good QEWI should welcome these questions. Their answers will tell us whether they see Local Law 11 as a box‑checking exercise or a long‑term partnership.

Local Law 11 can feel intimidating, but the mechanics are straightforward: know whether we’re covered, know our cycle, hire the right professional, plan repairs over time, and respond quickly when conditions become unsafe.

With a clear schedule, a competent QEWI, and reliable data on our NYC building violations through tools like NYC violation lookup tool and ViolationWatch, we can keep our facades safe, our tenants protected, and our buildings on the right side of DOB enforcement, cycle after cycle.

Key Takeaways

- Local Law 11 requires all NYC buildings over six stories to undergo a formal facade inspection every five years by a Qualified Exterior Wall Inspector (QEWI) and file a FISP report with DOB within their assigned sub-cycle window.

- Missing Local Law 11 deadlines or failing to correct Unsafe conditions leads to DOB violations, mounting civil penalties, extended sidewalk sheds, and potential Stop Work Orders that can disrupt operations and financing.

- Owners should treat facade work as a recurring capital plan by calendaring their cycle, running pre-cycle condition reviews, and budgeting in advance for access, professional fees, and repairs.

- Any sign of facade distress—such as cracking, spalling, loose railings, water infiltration, or damage after severe weather—should trigger an immediate professional review, even between formal Local Law 11 cycles.

- Choosing an experienced QEWI and coordinating closely with contractors, building staff, and tenants helps minimize disruption, control shed duration, and keep the building in long-term compliance with NYC facade safety rules.

Local Law 11 / FISP FAQ for NYC Building Owners

What is Local Law 11 and which NYC buildings must comply?

Local Law 11, also called the Facade Inspection & Safety Program (FISP), requires periodic facade inspections for NYC buildings greater than six stories. It applies to rentals, co‑ops, condos, commercial, mixed‑use, and institutional buildings citywide. Landmarked properties are not exempt and often require extra planning and approvals.

How often do I need a Local Law 11 facade inspection and filing?

Local Law 11 runs in repeating five‑year cycles. Each building is assigned to a specific sub‑cycle window based on its block number. Within that window, a Qualified Exterior Wall Inspector (QEWI) must complete the inspection and file a FISP report with DOB. Missing your window triggers violations and penalties.

What happens if I miss a Local Law 11 deadline or ignore an Unsafe facade?

If you miss your Local Law 11 filing or fail to correct Unsafe conditions on time, DOB can issue violations, monthly civil penalties, and fees tied to prolonged sidewalk sheds. In serious cases, DOB may issue Stop Work Orders and require emergency protection like sheds, fencing, or netting until hazards are repaired.

When should I request an extra facade inspection outside the normal Local Law 11 cycle?

You should call a QEWI or facade professional if you see widening cracks, spalled masonry, rusted or deflected lintels, loose stone, water infiltration from the exterior, or wobbly railings. Major storms, vehicle impacts, 311 complaints, or DOB/HPD violations tied to leaks or stability are also strong triggers for a targeted review.

How much does Local Law 11 compliance typically cost for a NYC building?

Costs vary widely by height, access complexity, and facade condition. Budgets usually include three buckets: professional/QEWI fees and filings, access and safety (sheds, scaffolds, rigging, permits), and repairs (masonry, steel, parapets, balconies). Older masonry buildings should plan for significant facade work at least every other cycle as a recurring capital expense.

What’s the best way to stay ahead of NYC building violations related to Local Law 11?

Start by confirming your building’s FISP sub‑cycle, last filed status (Safe, SWARMP, or Unsafe), and any open DOB or HPD issues. Set calendar reminders 18–12 months before deadlines, run periodic condition reviews, and use a NYC violation lookup or alert service so new facade‑related violations are caught and addressed quickly.