Walk down almost any New York City block and you’ll see it: two buildings side by side, same age, same basic construction, same zoning, yet one has a handful of open violations and the other is on every “bad landlord” list in town.

We tend to blame it on a “bad building” or a “problem owner,” but the reality is more complicated. NYC building violations pile up because of how properties are built, used, managed, financed, and watched, not just because of one leak or one missed filing.

In this piece, we’ll unpack why some properties reliably end up with 10× more DOB violations, HPD complaints, and enforcement actions than others. And just as important, we’ll look at what owners, managers, and investors can actually do to move a building from chronic violator to quiet, compliant workhorse in their portfolio.

How Building Violations Work And Why They Matter

At the most basic level, a violation is an official statement from a regulator that a condition at a property doesn’t meet code. In NYC, that could be the Department of Buildings (DOB), the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), the Fire Department (FDNY), or other agencies depending on the issue.

Common Types Of Building Violations

When we talk about NYC building violations, we’re usually talking about a few recurring buckets:

- Structural and exterior – Unsafe façades, cracked foundations, deteriorated balconies, loose brick, failing roofs. In NYC, Local Law 11 façade issues alone can snowball into multiple DOB violations.

- Life‑safety – Blocked exits, non‑functioning fire alarms or sprinklers, missing self‑closing doors, inadequate egress lighting. These are the issues that keep fire marshals up at night.

- Electrical, plumbing, mechanical – Overloaded panels, illegal wiring, improper venting, non‑code gas piping, broken boilers, unapproved HVAC work.

- Accessibility – Missing or non‑compliant ramps, elevator problems, doorway clearances that don’t meet ADA or local requirements.

- Habitability and sanitation – No heat or hot water, pests, mold, water leaks, broken windows, peeling lead paint, unsafe stairs and railings. These often show up as HPD complaints before they become formal violations.

Each of these categories can generate multiple separate tickets. A leaking roof that causes mold in three units and an electrical hazard in a ceiling can appear as a cluster of unrelated violations on paper.

How Inspections Are Triggered

One key reason some buildings rack up many more violations than others has nothing to do with bricks and mortar, it’s about how often inspectors show up and what prompts them.

Inspections are typically triggered in three ways:

- Reactive complaints

Most housing and building inspections in NYC start with someone raising their hand:

- Tenants call 311 to report no heat, leaks, pests, or unsafe conditions, which can lead to HPD or DOB inspections.

- Neighbors complain about illegal construction, noise, or sidewalk conditions.

- Police, fire, or social services refer a property after an incident.

- Proactive programs

Certain building types and risk categories are inspected on a schedule:

- Periodic façade inspections (FISP / Local Law 11) for larger buildings.

- Routine boiler, elevator, and sprinkler tests.

- Targeted sweeps in areas with high complaint volumes or known problem landlords.

- Permits and construction

Whenever work requires DOB permits, new construction, alterations, change of use, inspectors review plans and visit the site. If they find unpermitted work or unsafe conditions, that can generate DOB violations completely separate from tenant complaints.

The pattern is important: once a building is on regulators’ radar, more eyes means more discovered issues. Two buildings with similar defects can end up with very different violation histories simply because one generates more HPD complaints or draws more DOB attention.

For NYC‑specific rules and enforcement detail, DOB’s own resources are worth reading, including its “Buildings Information” portal and HPD’s Housing Maintenance Code enforcement overview.

The Real Costs Of A High‑Violation Building

We often talk about violations like they’re just paperwork. They’re not.

A heavy violation load can mean:

- Direct financial penalties – Civil fines, interest, and in some cases emergency repair charges that convert into municipal liens.

- Forced repairs on the city’s timeline – Vacate orders, partial vacates, or orders to repair that disrupt rent rolls and operations.

- Financing and transaction friction – Lenders and buyers look closely at open DOB violations and HPD complaints: chronic issues can reduce valuations or kill deals outright.

- Reputation damage – Being flagged as a “problem building” in the press, on advocacy maps, or in tenant forums makes leasing harder and invites more scrutiny.

- Health and safety impacts – At the neighborhood level, dense clusters of housing code violations correlate with higher emergency‑room use and worse health outcomes.

In short, NYC property compliance isn’t just a legal box to check. It’s a core business and risk‑management function.

Hidden Risk Factors That Drive Violation Volume

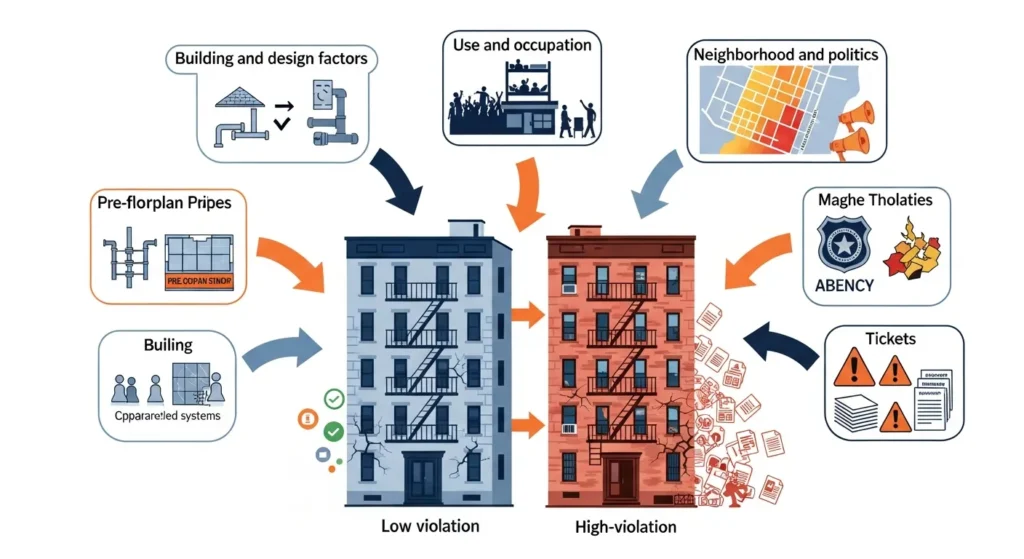

Why does one property end up with a handful of minor items while another nearby has pages of open violations? When we look across empirical studies and NYC enforcement patterns, the same underlying risk factors show up again and again.

Age, Design, And Construction Quality

Older buildings aren’t automatically bad actors, but they start the race with a few disadvantages:

- Wear and tear – Aging roofs, plumbing, and electrical systems create more opportunities for leaks, shorts, and failures.

- Pre‑code conditions – Many older properties predate modern fire‑safety and accessibility standards. When work is done, those older systems are suddenly judged against today’s codes.

- Original construction shortcuts – Where first builders cut corners, ignored manufacturer instructions, skipped inspections, used subpar materials, we see a long tail of DOB violations years later.

On the other end of the spectrum, newer multifamily buildings aren’t immune. National surveys have found surprisingly high rates of code issues in new apartments, townhouses, and condos. The pattern suggests a systemic quality‑control problem in some segments of the construction industry, not just “old building problems.”

Occupancy Type And Use Patterns

How a building is used drives both actual risk and how often people complain.

- High‑density rentals – Large multi‑family rentals with many low‑income tenants typically generate more HPD complaints. More people, more wear, and more dependency on the landlord for basic services like heat and hot water.

- Complex mixed‑use buildings – Properties combining retail, assembly spaces, and apartments juggle multiple code regimes, fire, egress, accessibility, and use‑group restrictions, which multiply the chances of NYC building violations.

- Short‑term rentals and informal uses – Illegal hotels, makeshift rooming houses, or after‑hours businesses in residential spaces often come with severe fire and egress violations once discovered.

Two buildings may share a structural blueprint, but if one is a quiet co‑op and the other is a high‑turnover rental with informal sublets and overcrowding, their enforcement trajectories will diverge fast.

Location, Neighborhood Pressure, And Politics

Where a building sits, geographically and politically, also matters.

Research in cities like Chicago has shown that neighborhoods with more low‑income and Black residents see denser clusters of serious violations. At the same time, city policy choices and enforcement priorities can concentrate inspections in specific areas or among certain landlord cohorts.

In NYC, we see this play out through:

- Targeted initiatives aimed at “worst landlord” lists or high‑complaint corridors.

- Community organizing and media attention that direct regulators toward particular buildings.

- Resource constraints at agencies, which mean inspectors are steered toward the highest‑visibility or highest‑risk cases rather than distributing attention evenly.

The upshot: enforcement volume isn’t purely a reflection of physical conditions. It also reflects who lives nearby, who’s organizing, and what City Hall cares most about in a given year.

Ownership Structure And Investor Strategy

How a building is capitalized and managed can be the single biggest predictor of whether it becomes a chronic violator.

Patterns we see again and again:

- Highly leveraged or speculative plays – Owners banking on fast appreciation may defer capital work, keep operating expenses low, and treat violations as a cost of doing business.

- Fragmented or absentee ownership – Complex LLC structures, out‑of‑state owners, or frequently flipped assets often correlate with weaker oversight and slower response times.

- Aggressive eviction practices – Studies have found that buildings with chronic serious violations are often owned by landlords who also file large numbers of evictions, signaling a broader strategy of squeezing operating margins.

By contrast, long‑term, hands‑on owners, including nonprofits and mission‑driven investors, may operate in the same neighborhoods but accumulate far fewer violations simply because they consistently reinvest, plan capital work, and respond to HPD complaints quickly.

Operational Habits That Attract (Or Repel) Inspectors

Once we move past age and location, daily habits are where we see the clearest difference between buildings with a manageable number of violations and those with 10× more.

Maintenance Culture And Deferred Repairs

Every portfolio has two types of buildings:

- Properties where superintendents log issues, management responds, and preventive maintenance is scheduled.

- Properties where everyone just waits until something breaks, or a tenant calls 311.

In the second group, minor defects stack up and interact:

- A small roof leak becomes ceiling damage, then mold, then electrical hazards.

- A loose handrail becomes a trip hazard, then an injury, then a lawsuit and DOB citation.

- Ignored boiler service leads to repeated heat outages, HPD emergency repairs, and civil penalties.

From an inspector’s point of view, these buildings look like they’re falling apart on multiple fronts, even if the root cause is a few unaddressed system failures.

Paperwork, Permits, And Record‑Keeping Gaps

Some of the most frustrating NYC building violations aren’t about the physical building at all, they’re about missing paperwork:

- Work done without required DOB permits.

- Expired permits that were never closed out with final inspections.

- Missing boiler or elevator inspection reports.

- Failure to post required notices.

Nationally, roughly a third or more of plans are denied on code issues, and close to half of field inspections uncover at least one violation. In a city as complex as New York, keeping clean records is itself a risk‑management function.

Buildings with lax administrative habits tend to:

- Trip over technicalities (e.g., a permit that lapsed mid‑project).

- Trigger more follow‑up inspections.

- Signal to regulators that broader non‑compliance may be lurking.

Contractor Choices And Oversight Failures

We all know the story: a low‑bid contractor promises to “take care of permits” and finish ahead of schedule. Six months later, there’s a stop‑work order on the door and a stack of DOB violations online.

Common failure points include:

- Unpermitted or out‑of‑scope work that goes beyond what was approved on plans.

- Ignoring manufacturer instructions on fire‑rated assemblies, sprinklers, or life‑safety systems.

- Using unlicensed trades for gas, electrical, or elevator work.

Owners and managers who don’t actively supervise scopes of work, verify licensing, and insist on proper close‑out set themselves up for chronic violations long after construction wraps.

Resident Behavior And Complaint Patterns

Residents aren’t passive actors in this story. Their choices shape both actual conditions and how often inspectors show up.

Examples we see routinely:

- Blocked egress from furniture, bikes, or storage in hallways.

- Illegal electric setups, daisy‑chained power strips, overloaded outlets, space heaters.

- Improvised partitions and additional occupants that affect fire safety and egress.

At the same time, resident behavior drives the complaint pipeline. In one studied neighborhood, tenants directly filed about two‑thirds of all complaints, with anonymous calls and referrals making up most of the rest.

Buildings with active tenant associations, legal support, or media attention will naturally log more HPD complaints and, hence, more documented violations. A similar building with less organized tenants may be just as deficient physically but look “cleaner” in city data.

If we want fewer violations without compromising safety, we need both better conditions and better communication with residents so they understand how to report genuine risks and avoid creating new ones.

Regulatory Complexity: When Codes Make Some Buildings Easy Targets

Even well‑run buildings can feel like they’re drowning in overlapping rules. The complexity of modern codes means some properties are simply more exposed than others.

Layered Codes And Conflicting Requirements

In NYC, a typical multi‑family building is subject to:

- The NYC Building Code.

- The Housing Maintenance Code.

- The Fire Code.

- Energy and mechanical codes.

- Federal and state accessibility requirements.

For mixed‑use or specialized buildings, the list is even longer.

Each code has its own enforcement unit, priorities, and inspection triggers. Renovate a lobby and you may touch egress, accessibility, fire separation, and energy efficiency, all at once. A misstep in any of those buckets can result in separate DOB violations.

From a risk standpoint, properties undergoing frequent renovations, change‑of‑use conversions, or tenant‑driven build‑outs are effectively walking through a minefield of overlapping rules.

High‑Risk Systems: Fire, Elevators, Facades, And Accessibility

Certain building systems draw intense regulatory attention for good reason:

- Fire protection – Sprinklers, standpipes, alarms, smoke detection, self‑closing doors.

- Elevators – Life‑safety critical and subject to regular testing and reporting.

- Façades – In NYC, façade inspections under Local Law 11 focus on public safety risks from falling debris.

- Accessibility elements – Ramps, lifts, door hardware, and common‑area layouts.

These systems are inspected more frequently and hold less tolerance for minor defects. A single faulty sprinkler head can trigger multiple related citations. So buildings that rely heavily on these systems, tall, complex, or highly trafficked properties, inherently have more exposure.

The city’s Facades Inspection & Safety Program (FISP) is a clear example: one adverse FISP filing can lead to repair orders, follow‑up inspections, and a string of related violations if owners are slow to act.

Change Of Use, Additions, And Grandfathered Conditions

Whenever we change how a building is used, we invite the entire modern codebook in the door.

- Conversions (e.g., office to residential, warehouse to studios) can require substantial upgrades to fire‑rating, sprinklers, and egress.

- Additions and enlargements can trigger contemporary accessibility and structural standards for areas that were previously grandfathered.

- Misreading grandfathering is a common trap. Owners assume older conditions are “legal as is,” only to discover that specific scopes of work require partial upgrades.

Buildings that go through complex repositionings or serial renovations without disciplined code analysis can rack up violations in waves: one batch when plans are filed, another during construction, and a third when final inspections expose unresolved legacy issues.

Why Two Similar Buildings Can Have Wildly Different Violation Records

On paper, two properties may look nearly identical: same block, same size, same vintage, same tenant demographics. Yet one has a modest list of historic violations, mostly closed, while the other appears chronic.

What explains the gap?

Comparing A “High‑Violation” And “Low‑Violation” Property

Let’s imagine a concrete example. Two six‑story walk‑ups in the same Brooklyn census tract:

- Both were built in the 1920s.

- Both house rent‑stabilized tenants with similar income profiles.

- Both experienced plumbing and roof issues over the last decade.

But when we pull official records, we see:

- Building A has 25 total DOB violations in 10 years, most for minor items, and a manageable volume of HPD complaints.

- Building B shows more than 250 violations across DOB and HPD, including repeat Class C (immediately hazardous) issues and a history of emergency repairs.

The physical differences are modest. The real differences are operational and strategic:

- Building A’s owner implemented a capital plan to replace the roof and risers, scheduled annual inspections, and responded to 311 calls quickly.

- Building B’s owner patched leaks, postponed major work, fought tenants in court, and let HPD emergency repairs accumulate.

Over time, enforcement trajectories diverged. Once Building B crossed a threshold, serious violations in multiple distinct years, it effectively became a “chronic” case in the eyes of regulators. Data from other cities suggest that after that point, most such buildings keep accruing serious violations and rarely self‑correct without a deliberate turnaround plan.

Management Practices That Make The Difference

Looking across portfolios, we see a set of consistent differentiators between low‑ and high‑violation buildings:

- Responsiveness to tenants – Do we treat HPD complaints and 311 calls as early warning signals or as annoyances to be ignored until a violation is issued?

- Capital planning – Are we proactively replacing end‑of‑life systems (roofs, boilers, risers), or waiting for catastrophic failure?

- Permitting discipline – Is every project properly permitted and closed with final sign‑offs, or do we leave a trail of open permits and unresolved objections?

- Contractor governance – Do we vet contractors for code literacy and compliance history, or pick only on price and speed?

- Documentation and follow‑through – After an inspection, is there a clear internal process to track orders, deadlines, and proof of correction?

In other words, the biggest drivers of whether a building ends up with 10× more violations are choices, not inevitabilities.

To keep a closer eye on where we stand, we can regularly review our properties’ public records. For free lookups, use our NYC violation lookup tool to see DOB violations, HPD complaints, and patterns across our own buildings or targets we’re underwriting.

How Data And Technology Expose Problem Buildings

A decade ago, most building‑code issues lived in paper files. Today, violations and complaints are searchable, mapped, and often analyzed by journalists, tenant advocates, and investors.

Public Databases, Violation Maps, And Open Data

New York City agencies have opened up remarkable amounts of information:

- DOB’s Building Information System and DOB NOW portals show permits, jobs, and violations for most properties.

- HPD maintains public data on complaints, violations, and emergency repairs.

- The city’s Open Data portal hosts downloadable datasets that let anyone map hotspots for housing and DOB violations.

This transparency cuts both ways. It allows responsible owners to benchmark performance and fix emerging patterns. But it also makes it easy to identify “bad actors,” which can amplify political pressure and invite more proactive enforcement.

Tools like ViolationWatch pull these disparate data sources together so we can see a building’s history in one place, spot trends, and prioritize follow‑up.

Predictive Analytics, Sensors, And Proactive Monitoring

We’re also seeing a slow but steady shift from purely reactive enforcement to more predictive approaches:

- Analytics – Agencies and researchers use indicators like past violations, HPD complaints, age, and neighborhood metrics to predict which buildings are most likely to develop serious safety problems.

- IoT and building sensors – Boiler monitors, leak detection, and smart meters can provide early warnings within our own operations, helping us fix issues before they ever generate a violation.

- Portfolio‑level dashboards – Owners and managers are building internal tools that track open violations, inspection dates, and recurring problem categories across dozens or hundreds of assets.

This is where NYC property compliance becomes a data problem as much as a legal one. If we don’t know our own numbers, where DOB violations are clustering, which systems fail most often, which buildings have persistent HPD complaints, we’re flying blind.

Get instant alerts whenever your building receives a new violation, sign up for real‑time monitoring with our building violation alerts so issues never sit unnoticed in a city database.

Using Violation History In Due Diligence And Valuation

On the investment side, violation records are increasingly treated as core underwriting data, not background noise.

When we evaluate an acquisition today, we typically look at:

- Volume and severity of violations – How many, of what class, over what time period?

- Resolution rate – Are issues quickly cured, or do violations linger for years?

- Patterns – Do we see repeated heat and hot water problems? Structural issues? Frequent illegal construction?

- Alignment with rent levels – Are chronic conditions at odds with current or projected rents?

Evidence from Chicago and other markets suggests that resolving violations is associated with higher achievable rents, one study found that a 10% increase in resolved violations correlated with around a 5.5% rent increase, after controlling for other factors. The logic is intuitive: safer, better‑maintained buildings command more demand and face fewer disruptions.

For NYC assets, folding violation data into our models is becoming as standard as looking at tax arrears or utility costs. A building with a heavy load of open DOB violations and HPD complaints isn’t automatically a pass, but it is a signal of higher cap‑ex needs, timeline risk, and potential regulatory conflicts.

Turning Around A High‑Violation Building

Once a building is labeled a chronic violator, the instinct is often to play defense, dispute citations, minimize admissions, and “wait out” scrutiny. That usually fails. The only durable way out is to change the underlying conditions and habits that generated the violations in the first place.

Diagnosing The Root Causes, Not Just Clearing Tickets

We can think of violations as the visible symptoms of deeper problems:

- If we see recurring leaks, the root cause might be obsolete risers, not just bad caulk.

- If HPD keeps writing Class C violations for no heat, the real issue might be an undersized or failing boiler, not just operator error.

- If DOB repeatedly cites unpermitted work, there’s probably a systemic breakdown in how projects are scoped and filed.

An effective turnaround starts with a diagnostic phase:

- Pull a complete violation and complaint history from DOB and HPD.

- Group by category and system (e.g., heat, plumbing, egress, façade).

- Identify recurrent patterns and map them to building systems and processes.

Clearing individual tickets without addressing those root drivers just resets the clock until the next round.

Prioritizing Life‑Safety And High‑Impact Fixes

Not all violations are created equal. From both a legal and ethical standpoint, life‑safety and habitability issues come first:

- Fire protection and egress.

- Structural stability.

- Electrical hazards.

- Heat, hot water, lead paint, and severe mold.

We’ve found it effective to build a triage list:

- Immediately hazardous – Fix now, even if it means temporary relocation or emergency contracts.

- Serious but stable – Schedule within months, with clear funding and contracts.

- Technical and administrative – Permits, paperwork, signage, filings.

This approach reduces the worst risks quickly and demonstrates to regulators that we’re serious, which can help when negotiating timelines for lower‑risk items.

Building A Compliance Roadmap And Maintenance Plan

Once safety‑critical issues are under control, we need to prevent relapse.

Key elements of a sustainable plan include:

- A sequenced capital roadmap – Multi‑year planning for roofs, risers, boilers, and façade work, aligned with both code requirements and asset strategy.

- Standard operating procedures – Clear internal workflows for handling inspection notices, violation letters, access requests, and proof‑of‑correction filings.

- Preventive maintenance schedules – Boiler cleanings, roof inspections, pest control, elevator service, documented and tracked.

This is also where technology helps. Using tools like ViolationWatch, we can track violations across properties, monitor status, and avoid letting deadlines slip through the cracks.

Training, Communication, And Resident Engagement

A building can only stay compliant if the people who live and work there understand what’s at stake.

On the staff side, that means:

- Training supers and porters to recognize code issues and escalate them.

- Making sure property managers know how to read DOB and HPD notices and what deadlines actually mean.

- Giving construction teams clear directives on permits, inspections, and documentation.

On the resident side, engagement can dramatically change the violation profile:

- Explaining how to report urgent issues directly to management first.

- Educating tenants about fire safety, egress, and why hallways can’t be used for storage.

- Creating transparent channels (email, text, apps) so residents see that complaints lead to action.

The goal isn’t to suppress HPD complaints at all costs: it’s to address real problems before they escalate into formal enforcement. Get instant alerts whenever your building receives a new violation, sign up for real‑time monitoring through our building violation alerts so there’s never a gap between the city issuing a ticket and us responding.

Designing Buildings And Portfolios To Stay Low‑Violation

The most efficient way to manage violations is to avoid generating them in the first place. That requires thinking about compliance not just at the building level, but at the design desk and across the entire portfolio.

Embedding Compliance Into Design And Construction

For ground‑up projects and major rehabs, we can hard‑wire code compliance into the process:

- Early code review – Involve experienced code consultants during schematic design rather than waiting for plan examiners to raise objections.

- Peer review and quality control – Second‑set reviews of life‑safety systems, egress paths, and accessibility before filing.

- Strict adherence to manufacturer instructions – Especially for fire‑rated assemblies, sprinklers, and mechanical systems.

- Third‑party special inspections – Use reputable inspectors who will catch issues before DOB does.

This upfront rigor can feel expensive, but compared with the costs of stop‑work orders, redesigns, and post‑occupancy DOB violations, it usually pencils out.

Portfolio‑Level Policies, Standards, And Benchmarks

At scale, NYC property compliance becomes a management discipline, not a series of emergencies.

Better‑performing owners often:

- Set maximum open‑violation thresholds per building and escalate when those are exceeded.

- Track key indicators like violations per 100 units, average closure time, and repeat‑violation rates.

- Standardize response timelines for various violation classes.

- Conduct internal audits before known inspection cycles (facades, boilers, elevators).

Having these standards on paper isn’t enough. We need regular reporting so executives, asset managers, and property managers all see the same numbers and feel accountable.

Working With Regulators Instead Of Against Them

Finally, buildings that stay low‑violation over the long term tend to treat regulators as counterparts, not adversaries.

In practice, that looks like:

- Providing access promptly and professionally when inspectors arrive.

- Communicating proactively about complex projects or phased‑compliance needs.

- Using agency guidance documents and public resources, such as DOB service notices and HPD’s Owner Resources, to interpret rules correctly.

This doesn’t mean rolling over on every citation. But it does mean building a reputation for good‑faith compliance and following through on commitments, which can influence how much discretion inspectors use when writing up borderline conditions.

Conclusion

Some buildings really do receive 10× more violations than others. But that gulf isn’t random, and it isn’t explained only by “bad luck” or older bricks.

Across NYC and other cities, we see the same drivers again and again: aging systems and design flaws, high‑density and complex uses, neighborhood politics and organizing, leveraged ownership strategies, weak maintenance cultures, sloppy paperwork, questionable contractors, and persistent resident complaints.

The good news is that almost all of these factors are manageable. When we:

- Treat violations as data, not just tickets.

- Prioritize life‑safety and habitability fixes.

- Invest in preventive maintenance and disciplined permitting.

- Use tools and open data to track patterns across our portfolio.

- Engage residents and regulators in good faith.

…we can pull even a troubled building back from “chronic violator” status and keep future projects on a much cleaner path.

If we’re not sure where our properties stand today, the first step is visibility. For free lookups, use our NYC violation lookup tool to see existing DOB violations and HPD complaints. Then, use ViolationWatch to monitor trends and catch issues early.

Violations will never disappear entirely in a city as complex as New York. But with the right strategy, we can make sure they’re rare, quickly resolved, and never the defining feature of our buildings or our reputation.

Key Takeaways

- NYC building violations cluster in certain properties not just because of age or “bad landlords,” but due to deeper factors like ownership strategy, maintenance culture, and how often inspectors are triggered by complaints.

- High‑violation buildings typically share hidden risk factors such as deferred capital work, complex or high‑density uses, aggressive financial leverage, and sloppy permitting and paperwork practices.

- Two seemingly identical buildings on the same block can end up with 10× different NYC building violations because one responds quickly to HPD complaints, plans system upgrades, and supervises contractors, while the other patches issues and lets problems compound.

- Turning around a chronic violator requires diagnosing root causes, prioritizing life‑safety and habitability fixes, building a multi‑year compliance and maintenance plan, and training staff and residents to prevent repeat issues.

- Treating violation data as an asset—using public databases, tools like ViolationWatch, and portfolio‑level benchmarks—helps owners keep NYC building violations low, support higher asset values, and avoid reputational damage.

Frequently Asked Questions About NYC Building Violations

Why do some NYC buildings get 10× more violations than others?

Buildings with 10× more NYC building violations usually combine multiple risk factors: aging or poorly built systems, high‑density or complex uses, leveraged or absentee ownership, weak maintenance culture, sloppy permitting, and active tenant complaints. Once inspectors focus on a “problem building,” more inspections often uncover even more issues, widening the gap.

What are the most common types of NYC building violations?

Common NYC building violations cluster around recurring categories: structural and façade issues, fire and life‑safety deficiencies, electrical, plumbing, and mechanical problems, accessibility noncompliance, and habitability issues like heat, hot water, pests, mold, or lead paint. One underlying defect, such as a roof leak, can generate multiple separate violations across these buckets.

How do tenant complaints and inspections affect a building’s violation record?

Most inspections start with 311 or HPD complaints from tenants or neighbors. Once a building is on regulators’ radar, more visits lead to more discovered issues, even if nearby properties have similar physical problems. Active tenant organizing, legal support, or media coverage can significantly increase documented violations compared with less vocal buildings.

What can owners do to turn around a high‑violation NYC building?

Owners should diagnose root causes instead of just closing tickets: analyze violation history by system, prioritize life‑safety and habitability fixes, create a funded capital plan, enforce strict permitting and contractor controls, and implement preventive maintenance. Clear processes for tracking NYC building violations and fast responses to 311 complaints are essential for lasting improvement.

How can investors use violation data when underwriting NYC properties?

Investors increasingly treat NYC property compliance data as core underwriting input. They look at volume and severity of violations, how quickly they’re resolved, repeated patterns like heat outages or illegal work, and how conditions align with current or projected rents. Heavy, unresolved violations usually signal higher cap‑ex needs, timeline risk, and potential regulatory friction.