If you own or manage a mid‑ or high‑rise building in New York City, facade violations are not a theoretical risk, they’re a when, not an if, unless we stay ahead of them.

Local Law 11 (now the Façade Inspection & Safety Program, or FISP) was born out of real tragedies caused by falling masonry and failing building elements. Today, NYC building violations tied to facades can trigger immediate safety measures, six‑figure repair projects, and mounting fines if we don’t act quickly.

In this guide, we’ll walk through how Local Law 11 works, what DOB violations on facades actually mean, how cracks turn into unsafe conditions, and what practical steps we can take to stay compliant, protect the public, and keep long‑term costs under control.

What Is Local Law 11 And Why Building Facades Are Heavily Regulated

Local Law 11, now formally the Façade Inspection & Safety Program (FISP), is NYC’s answer to a simple but unforgiving problem: pieces of buildings were falling on people.

In several high‑profile cases, pedestrians were injured or killed by loose brick, terra cotta, or other facade elements that worked loose over time. Those incidents pushed the City to carry out one of the strictest exterior wall inspection regimes in the country.

Under FISP, exterior walls aren’t just an aesthetic concern, they’re legally treated as potential life‑safety hazards. The NYC Department of Buildings (DOB) requires that qualified professionals inspect facades on a fixed schedule, certify their condition, and flag anything that could become dangerous.

Why this much scrutiny?

- Aging stock – Many NYC buildings are pre‑war masonry structures with complex cornices and ornamentation. They’re beautiful, but they don’t age gently.

- Harsh environment – Freeze‑thaw cycles, wind loads, pollution, and constant patch repairs all accelerate deterioration.

- Density and foot traffic – In Manhattan, a small piece of stone falling from 15 stories isn’t just a maintenance problem: it’s a public safety crisis.

DOB’s own facade safety resources make it clear: the goal is to catch issues long before they become falling‑debris events. That’s why NYC building violations tied to facades are treated more like safety orders than routine maintenance notes.

For background, DOB publishes FISP rules and bulletins on its Facade Safety pages, and those rules have been tightened repeatedly, especially around long‑term sidewalk sheds and repeat noncompliance.

Which Buildings Must Comply And How The Inspection Cycle Works

Local Law 11 doesn’t apply to every building. It targets the structures that pose the highest public risk if something goes wrong.

What buildings are covered

Under FISP, the law applies to:

- All buildings in NYC taller than six stories (seven stories and up)

- Including residential, commercial, mixed‑use, and institutional buildings

- Regardless of construction type (masonry, curtain wall, precast, etc.)

If our building is six stories or under, FISP doesn’t apply, but we’re still responsible for general safety and could still receive DOB violations or HPD complaints tied to unsafe exterior elements.

The 5‑year inspection cycle

FISP runs on cycles. Each cycle covers a five‑year period. Within that period, every covered building must undergo a “critical examination” of its exterior walls and appurtenances and file a formal report with DOB.

Key points:

- A Qualified Exterior Wall Inspector (QEWI) must lead the inspection.

- They examine all street‑facing and yard-facing walls, including balconies, parapets, fire escapes, and railings.

- The QEWI issues a report rating the building Safe, SWARMP, or Unsafe.

- The report is filed electronically through DOB NOW, and a Wall Certificate reflecting that status must be posted in the building.

DOB divides buildings into sub‑cycles based on block and lot to prevent everyone filing at once. The filing windows are publicly posted in DOB FISP bulletins and are enforced with late‑filing penalties.

Missing a filing window doesn’t just earn a slap on the wrist. It can trigger failure‑to‑file penalties, daily fines, and, if ignored long enough, more serious NYC property compliance actions like additional DOB violations or enforcement hearings.

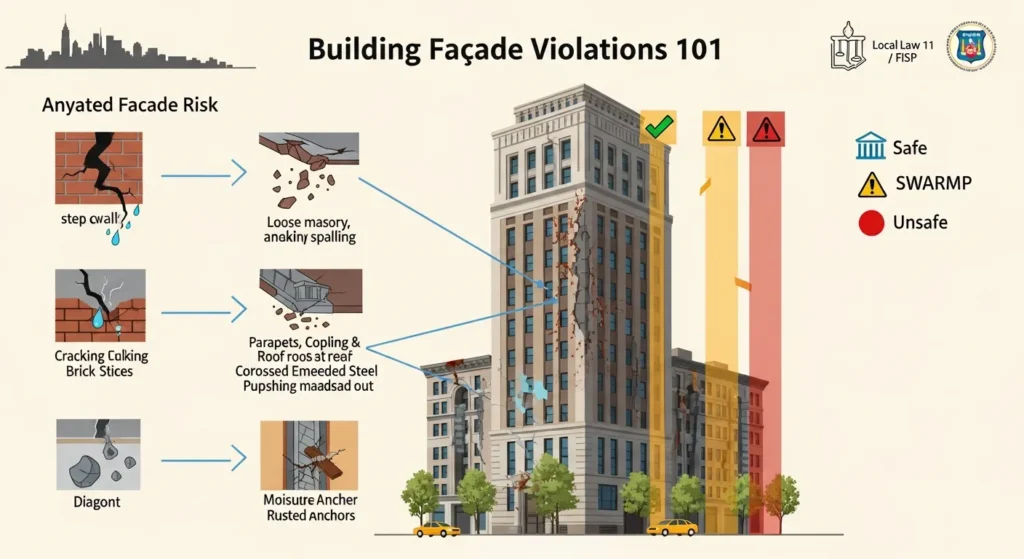

Understanding Facade Violation Categories: Safe, SWARMP, And Unsafe

When our QEWI completes a Local Law 11 inspection, they don’t just say “looks okay” or “needs work.” They have to assign one of three legal categories:

Safe

A Safe rating means:

- No hazardous conditions were observed.

- No known defects are expected to become unsafe before the next 5‑year cycle.

This is the ideal outcome, but it doesn’t mean we can ignore the facade for the next five years. Weather, leaks, and minor movement can quickly change conditions between cycles.

SWARMP (Safe With a Repair and Maintenance Program)

SWARMP is the gray area, and the one many owners misunderstand.

SWARMP means:

- The facade is not unsafe today, but

- There are defects or deterioration that will likely become unsafe if left alone.

Examples:

- Hairline cracks that are growing or showing signs of movement

- Early spalling of brick or stone

- Rust staining that suggests corroding shelf angles behind masonry

The QEWI must recommend specific repairs and a timeline, and we’re expected to complete those before the next cycle. If we don’t, those SWARMP items can, and often do, turn into Unsafe findings on the next report, along with violations and fines.

Unsafe

An Unsafe classification is serious:

- There is an immediate or reasonably foreseeable risk of falling debris or collapse.

- DOB is notified through the report, and usually via direct communication.

- Owners must provide immediate public protection (often a sidewalk shed) and start emergency stabilization.

Unsafe conditions almost always trigger DOB violations and ongoing oversight. Leaving them unresolved drives daily fines and, in some cases, additional enforcement steps like DOB enforcement actions.

From a risk perspective, we should treat SWARMP as a warning light and Unsafe as a red alarm. Waiting for a SWARMP defect to become “bad enough” is usually the most expensive strategy we can choose.

Common Facade Defects That Lead To Violations

Most facade violations don’t come out of nowhere. The same patterns repeat themselves across brick walk‑ups in Brooklyn, co‑op towers on the Upper East Side, and mixed‑use buildings in Queens.

Let’s break down the main culprits.

How Cracks Become A Serious Facade Safety Issue

Cracks are easy to shrug off, until they’re not.

Common crack issues include:

- Step cracks in brick or block following mortar joints

- Vertical cracks at corners, window heads, or slab edges

- Diagonal cracks suggesting movement or settlement

Alone, a hairline crack isn’t an automatic Local Law 11 violation. But combined with water, freeze‑thaw cycles, and structural movement, cracks can:

- Open pathways for water infiltration

- Lead to rusting of embedded steel (lintels, shelf angles, ties)

- Cause brick faces to pop off (spalling)

- Signal that parts of the wall are shifting out of plane

A QEWI will look at crack width, depth, pattern, and whether there’s evidence of active movement. If a crack is large, growing, or associated with displacement or bulging, it can tip a wall from SWARMP into Unsafe, especially above active sidewalks or entries.

Loose Masonry, Spalling, And Delaminating Materials

Loose or deteriorated masonry is one of the most common drivers of DOB violations under FISP.

Typical signs:

- Brick faces flaking or popping off

- Hollow‑sounding areas when tapped

- Pieces of stone or concrete on roofs, fire escapes, or sidewalks

- Visible gaps between masonry units

These conditions often trace back to:

- Long‑term water infiltration

- Poor past repairs (e.g., cement patches on soft brick)

- Corroded shelf angles or anchors expanding and pushing masonry outward

Once units start to delaminate, the risk of a sudden fall increases dramatically. That’s why inspectors are quick to call these Unsafe if they’re over public areas and not minor or isolated.

Defective Parapets, Copings, Cornices, And Ornamentation

The details at the top of the building cause a disproportionate share of headaches.

We see violations tied to:

- Parapets that lean, crack, or have loose brick/stone

- Copings that are cracked, displaced, or missing sections

- Cornices and decorative elements that have deteriorated connections

- Terracotta or stone ornamentation with visible cracks or missing pieces

These elements are directly exposed to the weather, repeatedly patched over decades, and often supported by old embedded steel. When that steel corrodes and expands, it can push outward, cracking or dislodging the masonry around it.

Because these components sit at roof level, a failure usually means falling debris traveling several stories before it hits anything. That’s why DOB and QEWIs treat parapet and cornice defects as high‑priority risks.

Water Infiltration, Rusting Anchors, And Hidden Structural Problems

Water is the root cause behind a huge percentage of facade problems.

Even when we can’t see the damage, inspectors look for indicators:

- Rust staining under windows or along shelf angles

- Efflorescence (white mineral salts) on masonry surfaces

- Staining and leaks at interior slab edges or columns

- Soft or crumbling mortar joints

Behind the wall, water can:

- Corrode shelf angles and anchors

- Rot wood framing (in older or hybrid structures)

- Degrade backup masonry or sheathing

As steel rusts, it expands, sometimes dramatically, pushing on the surrounding brick or stone. Over time this hidden corrosion can create bulges, cracks, and eventually unstable sections of wall.

QEWIs will often call for probes, small exploratory openings, to confirm what’s happening behind the surface. If they find extensive corrosion or structural compromise, they’re obligated to classify that area as Unsafe and recommend immediate stabilization and repair.

How Local Law 11 Inspections Are Performed

Understanding how a FISP inspection actually works takes some of the mystery (and anxiety) out of the process.

The Role Of The Qualified Exterior Wall Inspector (QEWI)

A QEWI is a:

- New York State Professional Engineer (PE) or Registered Architect (RA)

- Specifically approved by DOB to perform FISP inspections and file reports

Their responsibilities include:

- Planning the inspection scope and access (lifts, rope access, scaffolds)

- Performing both visual and close‑up examinations of all exterior walls

- Reviewing past reports, repair history, and any HPD complaints related to water leaks or interior damage that might signal facade issues

- Documenting conditions with photographs, sketches, and notes

- Classifying each facade as Safe, SWARMP, or Unsafe

- Filing the technical report through DOB NOW

We should think of the QEWI as our primary advisor for NYC property compliance on facade issues. Their judgment is what DOB relies on.

What Owners Should Expect During A Cycle 9 Inspection

Each cycle, the process is similar, even as rules evolve.

As owners or managers, we can expect:

- Pre‑inspection coordination

- Reviewing access points, roofs, setbacks, and balconies

- Clearing roof edges and terraces so the inspector can safely reach parapets and railings

- Sharing past FISP reports, violation history, and repair documentation

- Visual survey

- The QEWI walks the perimeter, adjacent roofs, and accessible setbacks.

- They use binoculars, cameras with zoom lenses, and sometimes drones (where permitted) to capture details.

- Close‑up examinations

- FISP requires hands‑on inspections of representative areas on all exposures.

- This usually involves suspended scaffolds (swings), rope access, or lifts to physically touch and probe the facade.

- Probes and testing (if needed)

- If there’s evidence of concealed issues, like corrosion behind brick, probes may be recommended.

- These are usually coordinated as part of a separate repair or investigation project.

The more organized we are, access, keys, roof cleanliness, records, the faster and smoother the inspection.

Typical Documentation, Reports, And DOB Filings

After fieldwork, the QEWI compiles a detailed FISP technical report, which includes:

- Building description and history

- Photographs of representative and defective conditions

- Maps or elevations marking where issues are located

- A condition rating for each facade (Safe, SWARMP, Unsafe)

- Repair recommendations and timelines for SWARMP conditions

- Required immediate actions for any Unsafe items

The report is submitted through DOB NOW: Safety, and once accepted, DOB issues or updates the Wall Certificate, which we must post in a conspicuous location in the building.

If DOB identifies discrepancies or thinks conditions are under‑classified, they may issue objections or conduct their own site visit. That can result in NYC building violations that we’ll see on DOB records.

To keep tabs on our status across all city agencies, many owners use ViolationWatch, which consolidates DOB violations, ECB/OATH cases, and other data. For free lookups, use our NYC violation lookup tool to see what’s currently on file for a property.

Receiving A Facade Violation: What Happens Next

Even diligent owners sometimes receive facade‑related DOB violations. What matters is how we respond.

Immediate Steps When An Unsafe Condition Is Found

When a QEWI flags an Unsafe condition in the FISP report, or DOB observes something unsafe itself, the clock starts quickly.

Typical immediate steps:

- Public protection

- Install sidewalk sheds, fences, or netting to protect pedestrians and adjacent properties.

- In many cases, this must happen within 24 hours of the Unsafe designation.

- Emergency stabilization

- Remove loose material that’s at risk of falling.

- Install temporary bracing, shoring, or netting where needed.

- Notification and coordination

- The QEWI and ownership team coordinate with DOB inspectors.

- Emergency work may require permits, but DOB usually prioritizes these applications.

We also want to alert our insurance broker and board or ownership group: significant facade issues often intersect with coverage and long‑term capital planning.

Timelines, Penalties, And Ongoing Fines For Noncompliance

DOB sets specific deadlines for:

- Filing the initial FISP report

- Correcting Unsafe conditions

- Submitting amended reports once work is complete

Missing these deadlines leads to:

- Failure‑to‑file penalties for missing the FISP window

- Ongoing civil penalties for Unsafe conditions that remain open

- Additional enforcement actions, including hearings at OATH

Recent rule updates, especially heading into 2025, have also targeted:

- Buildings that leave Unsafe conditions unresolved for long periods

- Properties that keep sidewalk sheds up for years without making real repair progress

DOB’s penalty schedules are public: we can review current fine structures and enforcement procedures on their violations page. The financial impact of long‑term noncompliance can easily exceed the cost of addressing the underlying facade work in a timely way.

Sidewalk Sheds, Public Protection, And Temporary Measures

Sidewalk sheds are a double‑edged sword:

- They’re essential for public safety and are often required whenever there’s an Unsafe facade condition above public areas.

- But they’re also expensive, disruptive, and increasingly a focus of city enforcement when they linger for years.

Key points for owners:

- Sheds and other protections must be properly designed, permitted, and maintained.

- DOB is tightening rules to discourage “forever sheds” that stand in for actual repairs.

- Neighbors, tenants, and community boards are applying more pressure on long‑term sheds, which can lead to added scrutiny and fines.

If we’ve received a violation tied to an Unsafe facade, we should assume our shed is temporary cover, not a strategy. The only real exit is a properly designed and executed repair program, signed off by our QEWI and accepted by DOB.

To avoid being surprised by new enforcement actions, many owners are moving to proactive monitoring tools. Get instant alerts whenever your building receives a new violation, sign up for real‑time monitoring with building violation alerts so we’re not the last to know when DOB takes action.

Correcting Facade Violations: From Emergency Repairs To Long‑Term Solutions

Once the immediate crisis is contained, shed up, loose material stabilized, the real work begins: designing and executing repairs that satisfy DOB, keep people safe, and make financial sense.

Prioritizing Repairs Based On Risk And Severity

We can’t always fix everything at once, especially on large or complex buildings. A smart plan ranks work based on:

- Life‑safety risk – Anything that could cause falling debris or collapse goes first.

- Rate of deterioration – Active rust, fast‑growing cracks, or accelerating leaks jump the line.

- Access efficiency – If we’re scaffolding an entire elevation, we should tackle as many known defects there as possible.

- Coordination with interior work – If we’re opening walls, we may want to align with interior renovations or window replacements.

Typically, we’ll start with areas labeled Unsafe, then address high‑risk SWARMP conditions, and finally knock out smaller or cosmetic items while access is already in place.

Coordinating Engineers, Contractors, And Building Staff

Effective coordination is what separates a manageable facade project from a nightmare.

Core team members include:

- QEWI / Facade engineer – Leads investigation, design, and DOB interface.

- Contractor – Executes repairs, manages scaffolds, and coordinates trades.

- Owner / board / property manager – Makes decisions, manages budget, communicates with residents and tenants.

- Building staff – Provides access, helps with logistics, and monitors day‑to‑day site issues.

Practical tips:

- Hold a kickoff meeting with all parties to review scope, schedule, and logistics.

- Establish a clear chain of communication for unexpected conditions and change orders.

- Keep residents and tenants informed: facades are noisy and disruptive, and good communication reduces complaints and HPD complaints about related issues like leaks or dust.

Best Practices For Durable, Code‑Compliant Repairs

The cheapest patch is rarely the cheapest solution over a 10‑ or 20‑year window. For durable, code‑compliant repairs we should aim for:

- Root‑cause fixes, not band‑aids

- Replacing or reinforcing corroded shelf angles, not just grinding and pointing the joint hiding them.

- Addressing roof and flashing issues that are feeding leaks into the facade.

- Compatible materials

- Using mortar and patch materials that match original properties (strength, permeability, color).

- Avoiding overly rigid cement mortars on soft brick that accelerate spalling.

- Proper detailing

- Flashings, drip edges, and weep systems that actually move water out instead of trapping it.

- Fully sealed penetrations for railings, anchors, and mechanical equipment.

- Thorough QA and sign‑off

- Regular site visits by the engineer during construction.

- Comprehensive punch lists and final inspections before demobilizing access.

Once work is complete, the QEWI files an amended FISP report showing that Unsafe conditions have been corrected. DOB then closes related facade violations and, if all is in order, our building’s status returns to Safe or SWARMP.

At that point, having a system like ViolationWatch watching our DOB, ECB, and HPD records helps confirm that everything has truly cleared and no surprise NYC building violations remain open in the background.

Preventing Future Violations With Proactive Facade Maintenance

The best way to handle Local Law 11 is to treat it as a minimum standard, not the full extent of our facade care.

Routine Inspections And Maintenance Checklists For Owners

We don’t have to wait for a QEWI every five years to know what’s happening on our walls.

Simple, recurring checks can catch early warning signs:

- Seasonal roof walks – Check parapets, copings, flashings, and sealant joints.

- Perimeter walks – Look for cracks, staining, spalling, and loose materials from the sidewalk.

- Balcony and terrace reviews – Inspect railings, slab edges, and waterproofing.

Basic checklist items:

- Missing or deteriorated mortar joints

- Cracks at corners, window heads, and slab edges

- Rust staining under windows or along horizontal bands

- Ponding water on roofs or terraces near parapets

Document what we see with photos and dates. Over time, that record helps us and our QEWI understand whether issues are static or progressing.

Monitoring Cracks, Movement, And Moisture Over Time

For borderline conditions, the question is usually: Is it moving?

Practical monitoring tactics:

- Crack gauges or simple pencil marks to track whether cracks are widening.

- Moisture meters or periodic infrared scans in leak‑prone areas.

- Tracking interior HPD complaints about leaks or mold and mapping them to exterior wall areas.

If we notice:

- Cracks that widen over a season

- New rust staining or efflorescence

- Recurring leaks at the same locations

…it’s time to bring in an engineer early, even if we’re mid‑cycle. Small, targeted repairs between cycles are almost always cheaper than emergency work triggered by an Unsafe finding.

Budgeting For Capital Work And Reserve Planning

Facade work isn’t a surprise expense: it’s a recurring capital obligation.

Good planning looks like:

- 20‑year capital plans that factor in facade cycles, major roof work, and window replacements.

- Reserves earmarked specifically for FISP‑related repairs.

- Coordinating facade work with other major projects (e.g., roof replacements or window upgrades) to leverage shared access costs.

Many co‑ops and condos now treat Local Law 11 as a fixed line item in their long‑term budgets. That mindset reduces the shock when a QEWI labels a wall SWARMP and recommends meaningful work within the next cycle.

From an information standpoint, staying ahead of NYC building violations across agencies helps shape those budgets too. Get instant alerts whenever your building receives a new violation, sign up for real‑time monitoring with building violation alerts so pending issues don’t surprise us at the worst possible moment.

And when we’re planning, we can always cross‑check open DOB and HPD issues with a quick search using our NYC violation lookup tool to make sure nothing falls through the cracks.

Conclusion

Local Law 11, and its modern form as FISP, exists because neglected facades can and do hurt people. For owners and managers, that reality shows up as DOB violations, sidewalk sheds, and high‑stakes repair decisions that affect safety, budgets, and property value.

If we understand how facades fail, what inspectors look for, and how Safe, SWARMP, and Unsafe categories really work, we’re in a much better position to plan instead of react. Regular maintenance walks, early‑stage investigations, and realistic capital planning turn FISP from a crisis‑driven headache into a manageable, recurring responsibility.

Eventually, NYC property compliance on facades isn’t about checking a box every five years. It’s about building a culture of vigilance, watching for cracks, leaks, movement, and complaints before they become violations. With the right professionals, a clear plan, and simple tools like ViolationWatch and our NYC violation lookup tool, we can keep our buildings safer, our sidewalks clearer, and our compliance record in far better shape for the long run.

Key Takeaways

- Local Law 11 (FISP) requires all NYC buildings over six stories to undergo a critical facade inspection every five years, with results officially classified as Safe, SWARMP, or Unsafe.

- Most building facade violations start as small issues—cracks, water infiltration, rusting anchors, and loose masonry—that escalate into Unsafe conditions and DOB fines if ignored.

- An Unsafe facade designation demands immediate public protection (typically sidewalk sheds), emergency stabilization, strict DOB timelines, and can trigger steep ongoing penalties for noncompliance.

- Addressing Local Law 11 facade violations smartly means prioritizing life-safety risks, coordinating closely with a QEWI, contractors, and building staff, and focusing on durable, root-cause repairs instead of short-term patches.

- Proactive maintenance—routine roof and perimeter walks, monitoring cracks and moisture, and long-term capital planning—helps owners stay ahead of building facade violations, control costs, and keep NYC property compliance manageable.

Building Facade Violations & Local Law 11: Frequently Asked Questions

What is Local Law 11 (FISP) and how does it relate to building facade violations in NYC?

Local Law 11, now called the Façade Inspection & Safety Program (FISP), requires NYC buildings over six stories to have their exterior walls inspected every five years by a QEWI. The inspector rates facades as Safe, SWARMP, or Unsafe, and Unsafe findings typically trigger DOB facade violations and required repairs.

What are the main differences between Safe, SWARMP, and Unsafe facade conditions under Local Law 11?

A Safe rating means no hazardous conditions are expected before the next cycle. SWARMP (Safe With a Repair and Maintenance Program) means defects could become unsafe if ignored. Unsafe means there is an immediate or foreseeable risk of falling debris, requiring sidewalk sheds, emergency stabilization, and prompt corrective work.

How do facade cracks turn into unsafe conditions and potential Local Law 11 violations?

Cracks allow water in, which can rust embedded steel, cause spalling, and push masonry out of plane. Inspectors look at crack size, pattern, and movement. Large, growing cracks or those tied to bulging walls—especially over sidewalks—can shift a facade from SWARMP to Unsafe and trigger building facade violations.

What happens after I receive a facade-related DOB violation for an Unsafe condition?

Once an Unsafe condition is identified, owners must quickly install public protection (often within 24 hours), stabilize loose material, and coordinate emergency permits and repairs. DOB sets deadlines for correcting Unsafe items and filing amended reports. Missed deadlines lead to daily civil penalties and possible OATH enforcement hearings.

How can I prevent future building facade violations and reduce the risk of sidewalk sheds?

Prevention starts with routine roof and perimeter walks, documenting cracks, staining, and spalling, and addressing leaks early. Monitoring movement and moisture, coordinating with a QEWI between cycles, and budgeting for cyclical capital facade work help keep conditions from deteriorating into Unsafe findings that require long-term sidewalk sheds.

How much do Local Law 11 facade repairs typically cost, and how should owners budget for them?

Costs vary widely: small targeted repairs can be tens of thousands of dollars, while major facade restorations on high-rises can reach six or seven figures. Owners should maintain 10–20‑year capital plans, earmark reserves for FISP work, and align facade projects with roof or window replacements to share scaffold and access costs.